We don’t have to go too deep into Facing the Past to discover that throughout the eighteenth century, there can’t have been very many people at all in Lancaster who did not have some form of connection with the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Not just the merchants directly engaging in it by either trading or transporting enslaved people; or making money from trading goods that were obtained by enslaved people; but everyone else whose job had a stake in sustaining that trade: the shipbuilders, suppliers of timber to build the ships, sailmakers, the sailors themselves. Then all the people who worked in the trades connected with products produced by enslaved people: from carpenters and cabinet makers in Gillows’s workshops, to those unloading sugar and rum on the quay, to those who traded in those goods.

What is really striking, as we walk around Lancaster today, contemplating just how much of the City was touched by the slave trade, is the connection that so many Lancastrians would have had with a tiny place half-way around the world. The islands of the Caribbean, and in particular the tiny St. Kitts and Nevis. Even by today’s standards, this is a long way away: 4,000 miles. Back in the eighteenth century, before steam ships were even invented, it would have taken a sailing ship up to nine months to get to St. Kitts from Lancaster. So even the most urgent of missions would have necessitated an absence from home of up to 18 months.

And yet a surprising number of people in Lancaster would have been familiar with this, and the other Caribbean islands. A typical crew would have been around 30 men. And then the traders themselves, and their families. And finally those Enslaved Africans, or people of African descent who were taken there, or - as in the case of Frances Elizabeth Johnson, taken from there and arrived here.

There’s a serious consideration here. Lancaster made its wealth during this time from trading goods that came from here. Both in enslaved Africans, but even more so in the products that enslaved Africans produced: sugar, mahogany, rum. And that was produced on islands such as St Kitts. Some of the families owned plantations here, others were based here as agents.

If Facing the Past was really to live up to its name, then as well as giving some form of agency to the 30,000 estimated Enslaved Africans who had all but disappeared from the history of the City; visibility needed to be created about St. Kitts itself. What is St Kitts like? What can we see today? What are the images of this island that all the protagonists from our story would have known? In short: we needed to create a visibility for St. Kitts in Lancaster.

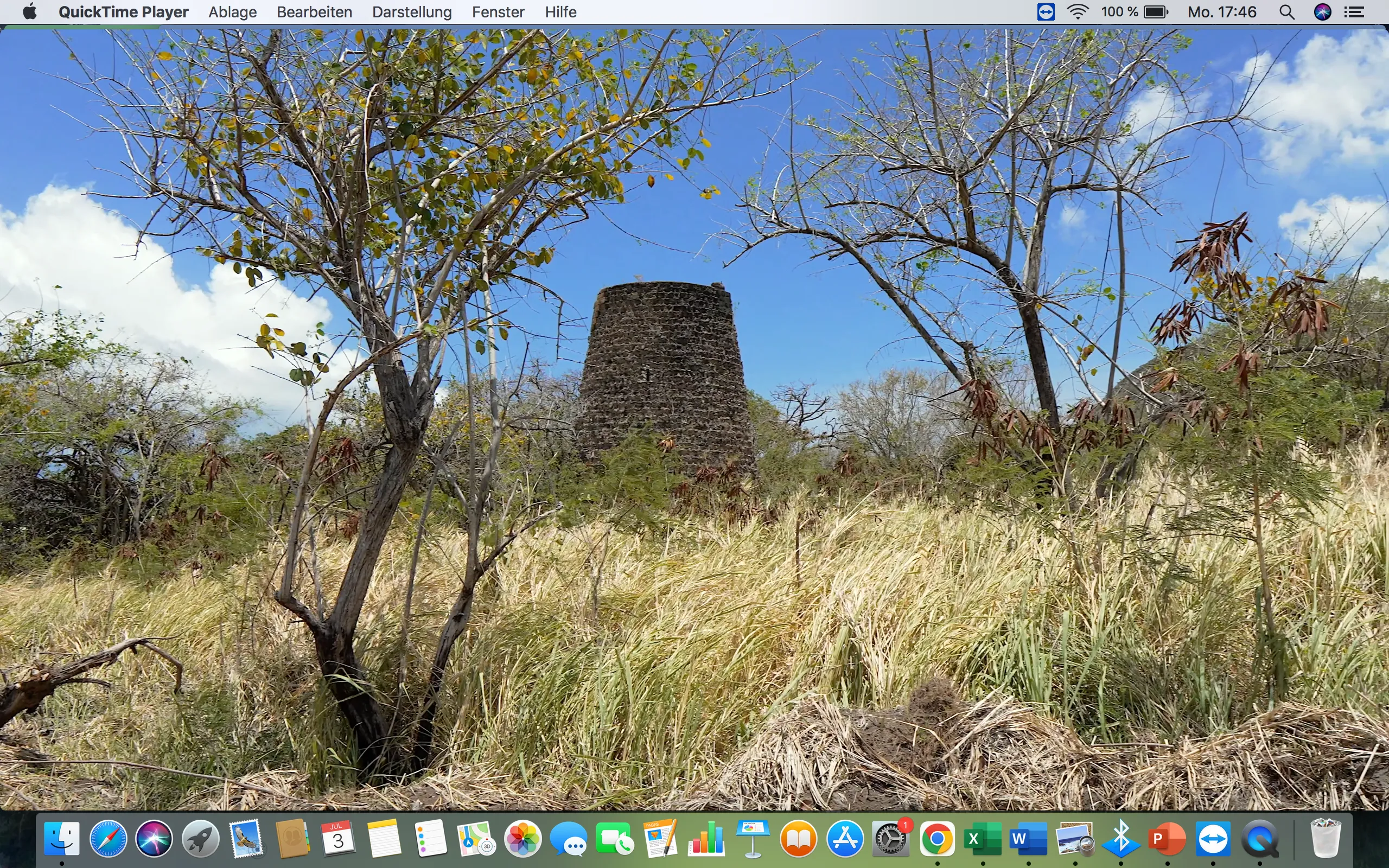

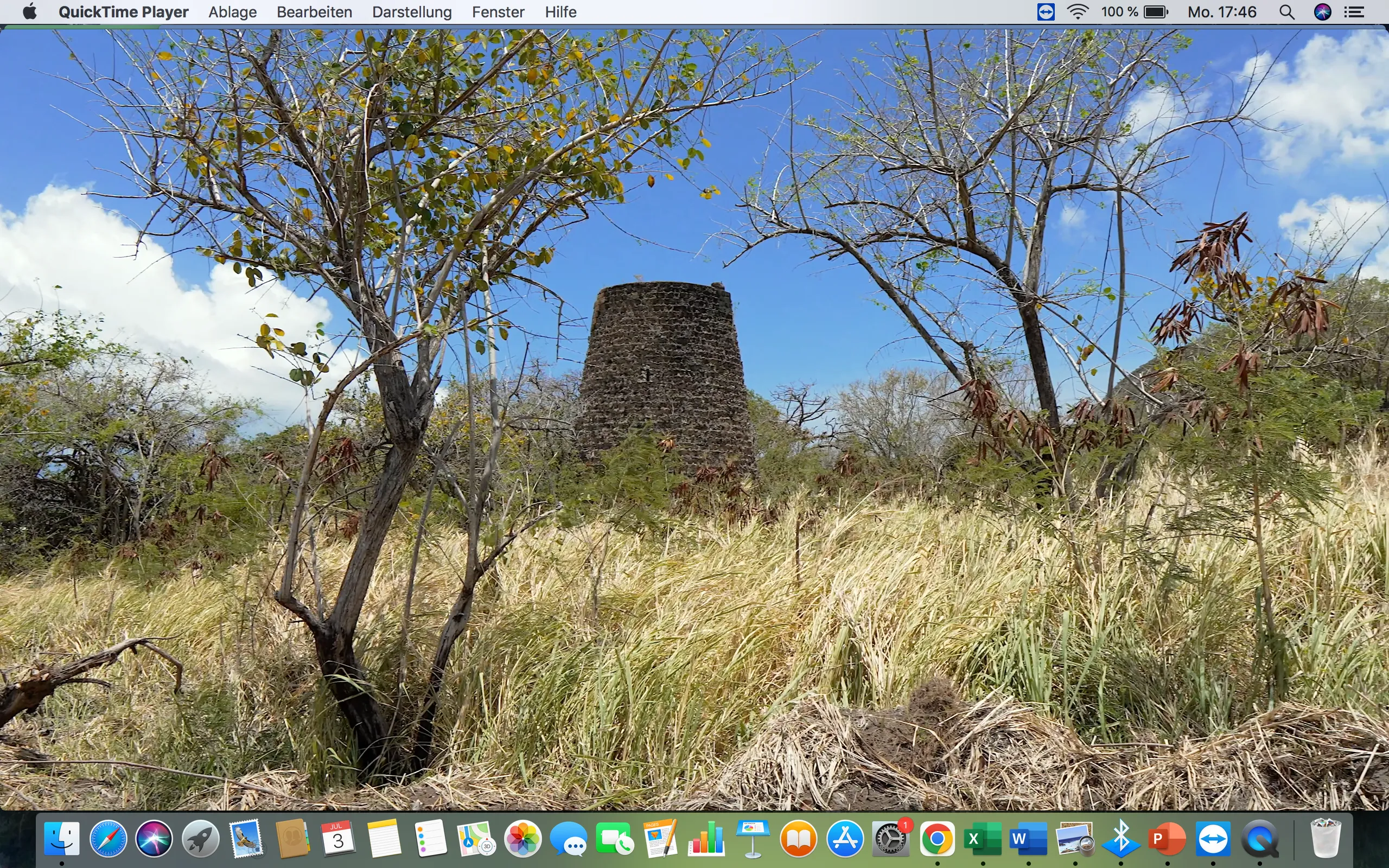

Our outreach research identified a professional agency based in Basseterre which sat at the intersection of photography, film and a commitment to using local talent. Stephen Smith, its proprietor, was keen to help. The only question was: Where should he go? For us, there was an obvious candidate: The Walk. The Walk was a plantation owned by the Rawlins family; Satterthwaites were familiar with it - indeed, this is where Polly Rawlins, who married Ben Satterthwaite, came from; and we can speculate that Frances Johnson would have been familiar with the plantation as an enslaved person - indeed, she might even have been enslaved on this very site. The plantation produced sugar and other goods that were directly transported to and traded in Lancaster, by Lancaster traders. So The Walk was an appropriate candidate. The only challenge was: could we even find it? Google Maps didn’t have any entry, and it was hard to try to locate it based on contemporary paintings.

However, a little research on the part of Stephen Smith did in fact locate it. A drive over to the other side of the mountain and down an old track, and there it was.

The films that we commissioned Stephen to make were all based on a simple brief: just a 360 degree rolling view of what is there now. The resulting work he generated is intensely moving. Because it’s all there: this tiny remote Caribbean island. Mountains and forests in the background, the sea in the foreground - and there, overgrown in the middle of everything: the remains of the actual sugar mill.

There is a strong, moving beauty to the site, and it is especially moving knowing that this is a view that so many of the people in our story would have known instantly: from Ben Satterthwaite all the way to France Johnson. The film was launched in Lancaster on epic scale, beamed on a massive projection screen in St. John’s Church during the Bank Holiday Weekend Facing the Past events in May 2023. There was something enormously fitting about premiering the work in the very place built largely with the fortunes made by the traders and families who extracted, processed and traded materials from that very spot; and others like it. That for many who were buried and commemorated on the walls of the church, this would have been a recognisable view, not to mention the materials (mahogany in the altar rails or the Gillows Organ case) that went into the church’s construction.

You can view the film by following this link https://go.humap.me/vryvjc